For an enhanced digital experience, read this story in the ezine.

In 1950, there were approximately 4,900 18-hole equivalent golf courses (18-HEQ) in the United States. Most had been commissioned by exclusive private clubs to serve the upper class, and only 3 percent had any residential real estate around them. In the post-World War II economic boom, the number of players increased from 3.5 million in 1950 to 11.2 million in 1970. During this period, the game was embraced by the new middle class who had the time, money and desire to engage in more recreational activities.

The catalyst for the symbiotic relationship between golf and real estate that sparked the boom in courses in the latter decades of the 20th century was the highly publicized Sea Pines Plantation development on South Carolina’s Hilton Head Island. Charles Fraser (who was a chair of the NRPA Board of Trustees from 1974 to 1975) undertook this development around 1960. Fraser demonstrated that golf courses could be designed so they created extensive amounts of green space and water around which building lots could be wrapped; and they could be threaded through less attractive land to enhance its value.

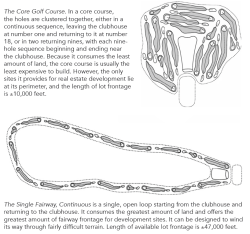

Fraser pioneered the concept of a residential golf community. This new focus on using golf to raise lot prices led to a change in the configuration of courses. Figure 1 shows that early “core” courses were compact, typically around 100 acres, with approximately 10,000 feet of edge. In contrast, residential golf developments typically constructed the “single fairway” configuration or adaptations of it. The residential configuration maximized the amount of edge by creating building lots on both sides of fairways, so there is typically about 47,000 feet of edge.

In 1970, there were 7,516 18-HEQ courses. At their peak in 2005, the number had almost doubled to 14,990, and a large majority of the new courses were the focus of residential golf communities. In 1987, the McKinsey & Company consulting firm published Strategic Plan for the Growth of the Game, which projected substantial increases in the number of golfers and called for “A Course a Day” to be built to accommodate it. The plan received extensive publicity in the media, was embraced by many in the development community and reinforced the momentum to build new courses.

Why Has Golf Declined?

While McKinsey continued to be optimistic in its updated 1999 report, that optimism ultimately proved to be unfounded. Since 2003, there has been a consistent annual decline in the number of golf players. There were 6.8 million fewer golfers in 2018 compared to 2003 — a loss of 22 percent. This resulted in a net reduction of 1,243 18-HEQ courses between 2005 and 2018. The decline is a function of the high cost of playing, difficulty of courses, and the game’s incompatibility with contemporary lifestyles.

Restore Property Values of Failed Golf Courses

In a typical year, approximately 200 courses fail. When a course fails, homeowners who have paid a premium to locate adjacent to it lose a substantial portion of their equity. The challenge is exacerbated by many failing courses being built on land that is proscribed from development either by local zoning ordinances seeking to preserve open space or by deed restrictions intended to protect owners who paid a premium to live near a golf course.

Changes are contingent on winning approval from homeowners associations or local governments, involve compromise and, inevitably, are politically and socially contentious. Strategies for retaining value include converting courses to parks or aesthetically appealing open spaces and reconfiguring courses by processes, such as downsizing.

Convert Courses to Appealing Open Spaces

The proportion of golfing households in a golf community has been variously reported as ranging from 10 percent to 30 percent. The appeal to the majority of residents is not golf — instead, open space, beauty/aesthetics and exclusivity are the defining attractors. For the 70 to 90 percent of residents, developers are not selling a golf course, rather they are selling a view and ambience.

If the course is converted to a park or appealing open space, the lot premiums will be akin to those of a passive park and lower than those associated with a viable manicured golf course. However, they will be higher than if no intentional redesign is undertaken, so the abandoned course is neglected and becomes a vacuum of unsightly open space. Conversion to public open space substantially reduces owners’ adverse impact on equity.

Further, there is growing acknowledgment of the damage golf courses can inflict by changing existing open space ecology; denigrating wetlands, sensitive aquifers or habitat; or contributing to runoff carrying pesticides, fungicides, herbicides and fertilizers. The replacement of courses with natural areas is consistent with society’s growing interest in protecting the environment.

Reconfigure Courses

Reconfiguration of a failing course is likely to involve downsizing it from 18 to nine holes. The process will likely involve development of additional home sites on some of the area. This generates the money needed to reconfigure, renovate and update the course, as well as transform some of the land into a park or open space. There is often tremendous political and emotional resistance to removing a golf course completely. A partial conversion may circumvent that resistance because it results in the improvement of the residual golf component, creates accessible public open space and provides some benefit to all the stakeholders.

John L. Crompton, Ph.D., is a University Distinguished Professor, Regents Professor and Presidential Professor for Teaching Excellence in the Department of Recreation, Park and Tourism Sciences at Texas A&M University and an elected Councilmember for the City of College Station.