Community participation in park planning is all the rage: it’s in our legislation, our policies and our thoughts as a cornerstone to modern park management. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Protected Area Governance and Management publication states: “Participation has become a basic principle of protected area planning, since it has been recognized that without participation by the beneficiaries of the plan, implementation and outcomes will often fail.”

Yet, even with community participation, implementation often fails. For example, since 1990, the staff at Yellowstone has written seven consecutive winter-use plans, following all National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) rules for public participation. This participation, however, has resulted in lawsuit after lawsuit, relegating those plans to gathering dust on the office shelf. If that can happen to the eminent Yellowstone, what about uncountable other parks around the world? In 2010, one well-cited management effectiveness study showed that 30 percent of protected natural areas worldwide suffer from poor management, for which one major factor is unimplemented plans.

Since “participation” can mean so many things, if planners and participants don’t jointly define what they mean by it, they can end up being dissatisfied with the outcome. Stacie Smith, senior mediator at the Consensus Building Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has facilitated planning and conflict management processes at numerous parks and heritage areas, and says that just following NEPA participation rules does not ensure meaningful public or stakeholder engagement in decision making. She recommends tools, several of which circulate on the internet, that define participation; for example, the International Association for Public Participation’s Public Participation Spectrum, which defines levels of participation. These tools clearly show that participation varies widely in form, from only telling the community what planners will do, to relinquishing control to the community to make decisions, and everything in between.

But even if planners define participation and align their expectations with those of participants, that still falls short of what planning demands for success in a dynamic, impossible to completely understand, complex, and ever-changing (DICE) world. Steve McCool, emeritus professor of wildlands management and planning at the University of Montana, says, “Decades ago, parks held both the legal power to plan and political power to implement their plans. Today, they retain the power to plan, but political power to implement is now held outside the agency.” The DICE world is marked by reduced budgets, greater diversity of public demands and more complex, messy problems. It requires that parks plan adaptively as their conditions continuously change and more holistically to consider parts of reality that before they may have ignored. To achieve this, they also need a new measure of plan success.

Measuring Plan Success

In many parks, managers measure park planning success by the percentage of planned tasks completed. In Costa Rica, for example, park managers are still partially evaluated based on this number. Since the 1960s, planning academics have decried measuring “conformance,” the degree to which implementation conforms to planned tasks as outmoded in a world that changes rapidly. What we plan in January may not be what we intend to do by, say, September. In 1997, two researchers (Hans Mastop at Radboud University and Andreas Faludi from Delft University of Technology, both in The Netherlands) proposed to measure plan “performance,” which includes the following:

- Conformance (percentage of planned tasks completed)

- Plan quality (degree to which plans contain sections, like zoning, consistent with expert recommendations)

- Planned achievements (objectives met)

- Unplanned achievements (other significant but unplanned achievements that emerge from the planning process, such as the creation of a new community organization)

- Plan influence on decision making (degree to which decision makers refer to the plan, even if they do not follow planned tasks specifically)

- Plan contribution to planning practice (degree to which subsequent planning processes adopt lessons from a previous process).

Director of Recreation for USDA Forest Service Southwestern Region Francisco Valenzuela cites the Prescott National Forest in Arizona as a model for public lands management, in which the Forest Service collaborates deeply with local governments. For example, the service works with the Verde Front community to protect and enhance the Verde River, which flows through the forest, but often not within the formal national forest boundaries. Recognizing that the Verde River and its tributaries will benefit from a regional approach to recreation, the service participates in a broadly supported, regional collaborative coordination, planning and implementation process across the Verde Valley. The community feels such ownership that it considers the recreation plan to be its plan rather than the service’s. The community contributes more than one-third of the money and labor needed to manage the program.

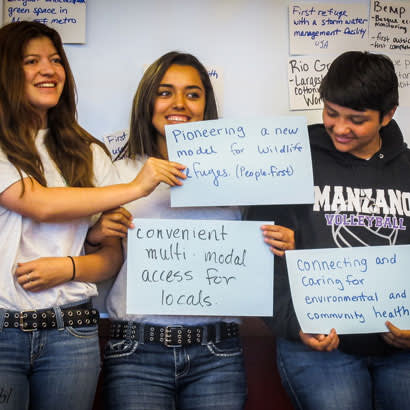

Building Community Capacity to Plan and Implement

Building a community’s capacity to plan and implement that plan also requires building community social capital and resilience, qualities that are farther along the participation spectrum. Working across organizations, interest groups, ethnicities and political stripes does not come naturally. To collaborate requires that the park community first have a minimal level of trust in the stakeholders at the table, and they must have minimal competence to dialogue together to create a shared vision and manage conflict.

Conflict is inherent in most planning decisions — not just conflict between parks and stakeholders (for example, over proposed management policies), but often conflict within park staff as well. According to Smith, “There’s often internal conflict within parks that is not being addressed or managed and contributes to challenges in a park achieving its goals and objectives or even aligning its goals and objectives across its own divisions.” Since internal relationships can directly affect implementation of any plan, Smith says, “It is frequently helpful, if not necessary, to surface points of conflict. Some of those points might be addressed within the planning process, while others may require additional work. But either way, we need to acknowledge that conflict. Ignoring it and pretending it’s not there is a recipe for plans that cannot be implemented.”

Beyond public participation, successful adaptive planning in a DICE world calls for:

- Creating a management plan of reasonable technical quality co-owned by the community

- Building the park community’s social capital, trust, motivation and ability to work together on an on-going basis

- Establishing conditions for adaptive and continuous planning, such as the plan format itself

Rise of Holistic Planning

Holistic planning considers the interior dimension of people (psychology) and groups (culture), as well as exterior aspects of plan quality, strategies and skills. It is an approach to planning that

- Recognizes emerging phenomena and interprets them through interior and exterior perspectives

- Redistributes political power by integrating different forms of knowledge and implementing democratic reforms

- Transforms constituency visions into reality through authentic conversation that defines many facets of visitation

- Cultivates constituent communities and strengthens their social capital, cohesion and trust to learn from and implement management decisions, with sufficient adaptability to protect heritage value and share them with the wider public over the long term

Public participation cannot be limited just to public hearings and 30-day comment periods. People only protect what they care about. Francisco’s voice rises in intensity, “When you have a public meeting and people are emotional and excited, that is a good sign. They care. We may not agree with them as land managers, but their showing up means that they care. The worst possible thing is to hold a public meeting and no one shows up at all.” But hey, at least they offered the public a chance to participate, right?

Jon Kohl is Executive Director of the PUP Global Heritage Consortium.