Revitalizing the Los Angeles River once offered hope for a more sustainable, livable and socially just city. There is growing evidence, however, that green displacement is destroying equal opportunity along the river. As neighborhoods become greener, more desirable and more expensive, people who have fought epic battles for a better life for their children, families and neighbors through parks, schools, green jobs, climate justice and river revitalization can no longer afford to live or work nearby.

Our nation was founded on the ideal that all of us are entitled to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Government agencies and recipients of public funding must distribute the L.A. River revitalization benefits and burdens fairly for all residents. Civil rights strategies by the people offer hope along the river and beyond. That’s how the people won victories at L.A. State Historic Park, Río de Los Angeles State Park, Baldwin Hills Park and the San Gabriel Mountains National Monument.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ (USACE) $1.4 billion plan to green 11 miles of the 52-mile L.A. River documents that there is not enough park space in the county for people of color and low-income people. This lack of park space contributes to related health disparities, and recipients of public funding need to ensure equal access to benefits from revitalization and compliance with civil rights and environmental justice requirements. The plan, generally a best-practice example for equitable planning, does not adequately address displacement, recreation and climate change.

Displacement and Gentrification

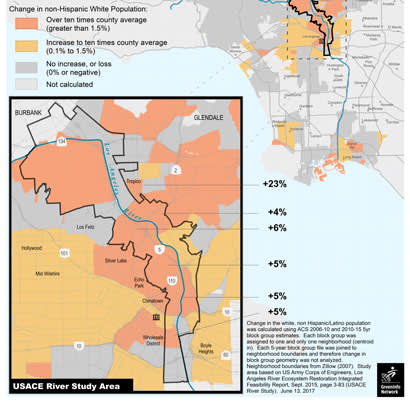

The USACE recognizes that gentrification could cause significant impacts to people through river revitalization, but states “no clear trends have emerged.” However, there is a disturbing pattern of displacement along the river in the 11-mile USACE study area. The percent, number and density of non-Hispanic white people has increased dramatically, even as their presence has declined 0.15 percent throughout the county from 2006 to 2015. In Trópico in northeast L.A., for example, the density of non-Hispanic white people has increased 168 percent, while dropping 19 percent for people of color, and incomes have increased significantly — 18 percent.

Diverse allies promote equitable river revitalization through the framework outlined in Equitable Redevelopment for the Los Angeles River (2017). Community goals include healthy, safe parks and recreation, affordable housing, thriving wages, opportunities for diverse enterprises, environmental remediation and funding to prevent displacement. Standards and data to measure equity and progress hold officials accountable and allow for planning and midcourse corrections. “Park poor” and “income poor” standards to invest funds under state law, the L.A. County Department of Public Health study of parks and health, and the County Parks and Recreation Needs Assessment offer methods to prioritize communities with the greatest needs.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, gentrification, the transformation of neighborhoods from low to high value, can displace longtime residents and cause businesses to move because of higher rents, mortgages and property taxes. These housing, economic, health and justice issues affect a community’s history and culture and reduce its social capital. Gentrification and displacement often shift a neighborhood’s characteristics — racial or ethnic composition and household income — replacing existing businesses and housing in underserved neighborhoods with new retail and commercial establishments and higher-cost housing. This threatens the social fabric of marginalized communities and exploits their vulnerabilities, reducing their resilience and adaptive capacities. Communities become more susceptible to economic, political, social and environmental shocks and transformations, including the decline of neighborhood networks and support structures.

Displacement exacerbates disparities by limiting access to housing, places to play and exercise, quality schools, healthy food, transportation, medical care and social networks, according to the report Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (2017). Displaced residents once again move to areas lacking resources, and displacement can result in financial hardship, reducing income for essential goods and services, and even lead to homelessness. To promote equity, this report offers recommendations on affordable housing, access to parks and recreation, avoiding displacement and civil rights strategies.

The High Line park in New York has become an icon of displacement and inequality. Co-founder Robert Hammond says, “We failed” to serve the community. “I want to make sure other people don’t make the mistakes we did.” The High Line, which saw nearby property values spike 103 percent, disproportionately serves non-Hispanic white people and tourists. Urban planner Ryan Gravel proposed the BeltLine in Atlanta, driven by a vision to ensure that people of all income levels could live along the 22-mile green corridor. Gravel recently resigned from the board over the lack of affordable housing, inclusivity and equity. Mark Pendergrast explores what went wrong in his book City on the Verge: Atlanta and the Fight for America’s Urban Future. Displacement is segregation, according to Peter Moskowitz in his book, How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood. Many activists and academics against displacement are themselves gentrifiers, according to the book Gentrifier by John Joe Schlichtman, Jason Patch and Marc Lamont Hill.

An alliance of environmental justice, environmental and civil rights activists and organizations have asked the U.S. EPA and the city of L.A. to review recipient compliance with civil rights mandates in river revitalization. The city admits that the river flows through the “epicenter of cancer risk” and that people of color and low-income people disproportionately lack park access and suffer from health vulnerabilities. To date, the EPA has not properly addressed compliance and enforcement. River revitalization through a straightforward civil rights compliance and equity plan provides the perfect opportunity for the EPA to take meaningful action to implement its own Environmental Justice 2020 Action Agenda and recommendations of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

River L.A., a nonprofit established by the city and a recipient of taxpayers’ grant funds, agrees displacement, recreation and climate are critical to the planning process. It, nevertheless, maintains that “nothing requires equity.” Pressed to comply with civil rights laws promoting opportunity and prohibiting discrimination, its response was that “First and foremost, we are not a government agency.” That doesn’t matter. Civil rights, environmental justice and health equity laws apply to recipients of state and federal financial assistance, and set standards for planning, participation and equitable outcomes. It’s not up to River L.A. to decide if it’s doing enough.

The following framework promotes equitable planning, participation and outcomes, and compliance with civil rights, environmental justice, and health equity laws and principles. It is discussed in the National Academies’ report and in Equitable Redevelopment for the Los Angeles River, and is summarized in Take Action Comics: The City Project by Sam García.

- Explain what you plan to do – for example, revitalize the L.A. River.

- Analyze the benefits/burdens for all.

- Consider alternatives to what is planned.

- Engage people of color and low-income people at every step of the process.

- Implement a plan to distribute benefits/burdens fairly and avoid discrimination.

Recommendations

L.A. River revitalization must expand opportunities for everyone to enjoy safe and healthy parks and recreation, fair housing, quality education, quality jobs and climate justice. People have the right to hold officials and recipients accountable for fair use of taxpayers’ dollars. We must watch the impact of projects on the ground to guard against discrimination, even when it’s subtle, implicit or not intentional. Displacement is discrimination, exacerbating the legacy and pattern of segregation, and discrimination is illegal. Equitable planning and civil rights strategies allow everyone to live in a healthy community, free from environmental degradation and discrimination.

Government agencies do not hesitate to turn to the courts to protect their interests. Everyday people have the same right to hold government accountable when planning fails. Communities of color and low-income communities traditionally have the least resources and political power. Discrimination is a major barrier to opportunity, holding people back from pursuing their dreams, and we are responsible for eliminating it. The following recommendations would greatly reduce displacement and discrimination:

- Recipients of public funding must distribute the benefits and burdens of river revitalization fairly, relying on the equitable planning framework.

- Government must ensure equal opportunity, free from discrimination.

- State and local agencies need to comply with and enforce civil rights, environmental justice and health equity requirements.

- Federal agencies need to comply with and enforce these laws.

- We must use the laws and regulations we already have to ensure equitable development and equal opportunity: California Government Code 11135, Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the President’s Executive Order 12898 on environmental justice and health equity, and others.

- Funders need to promote equal access to publicly funded resources for all.

- We the people must organize and stand up for our rights.

Together we must remove barriers to opportunity for everyone along the L.A. River and beyond.

Robert García is Founding Director-Counsel for The City Project.

Tim Mok is the Juanita Tate Social Justice Fellow for The City Project.