In his last week in office, President Barack Obama granted national monument status to two historic civil rights sites in Alabama, and a third site in South Carolina. He also expanded two existing national monuments in California and Oregon to add landmarks along the Pacific Coast and a significant mountainous landscape that is recognized for its exceptional biodiversity.

But, it was his actions a week earlier — Obama’s declaration of two national monuments in Utah and Nevada totaling almost 1.65 million acres — that has moved national monuments and other federal designations into an ongoing debate about presidential authority and the role of Congress to save special places.

Obama wrapped up his conservation legacy by designating more national monuments than any of his predecessors, including a balance of historic sites primarily focused on human rights and landscapes like Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, which protects 87,600 acres of Maine forestland from eminent development threats, and Bears Ears National Monument, a 1.3-million-acre landscape in southern Utah with important archaeological sites. While preservationists and conservationists have lauded his efforts, a number of lawmakers have taken to undoing the 1906 Antiquities Act that gave Obama, and all presidents since 1906, the authority to grant national monument status.

The Antiquities Act

The Antiquities Act, passed by Congress and signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt, was immediately used to protect a monolithic rock feature in Wyoming through the designation of Devils Tower National Monument. Roosevelt went on to proclaim more than a dozen national monuments, including Muir Woods National Monument in northern California, saving it from logging threats, and Grand Canyon National Monument, which was later expanded by Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt through the Antiquities Act and eventually named a national park by Woodrow Wilson.

In fact, many well-known landmarks were initially protected through presidential proclamation: Zion (Taft, 1909 and F.D. Roosevelt, 1927), the Statue of Liberty (Coolidge, 1924), Arches (Hoover, 1929), Denali (Carter, 1978), Grand Staircase-Escalante (Clinton, 1996) and World War II Valor in the Pacific (G.W. Bush, 2008). Many were later expanded and renamed through congressional legislation.

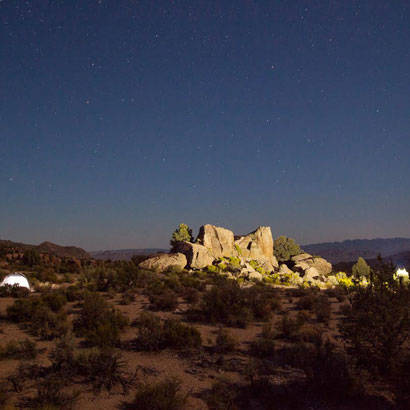

President Obama’s proclamations in late December of Gold Butte, a 300,000-acre national monument in southern Nevada, and Bears Ears in southern Utah fired up a long-simmering dispute about the Antiquities Act. Nevada’s Republican Senator Dean Heller and Congressman Mark Amodei filed legislation in early January, which, if passed, would restrict future national monuments from being created in Nevada without congressional approval. In Utah, the governor, federal and state lawmakers have vowed to undo Obama’s designation of Bear’s Ears or, at the very least, to drastically reduce the protected acreage.

While political posturing and legal opinion about completely undoing a national monument seem in direct conflict, reducing the size of a national monument has been undertaken in a few instances. Legal experts maintain that presidential use of the Antiquities Act must identify historic, cultural and scientific resources and that the boundaries of the national monument be adequate — but not far extended — to protect those resources.

Yes, Congress could overturn a president’s decision to create a national monument but that is highly unlikely. According to Colorado law professor Mark Squillace in a February article in the Christian Science Monitor: “It turns out that the designation of national monuments is very popular with the public.”

Top Down or Bottom Up?

The route to creating a national monument is typically arduous and often takes years. To be considered, the site must be nationally significant and meet a defined list of criteria. According to the National Park Service, it must be an outstanding example of a specific type of resource, it must illustrate or interpret cultural or natural themes, must provide opportunities for scientific study or recreational use, or must be relatively unspoiled. In 1936, advocates began calling for the area, now known as Bears Ears, to be given special designation. Area native tribes began advocating for national monument status in 2008.

So, how does the process begin? Typically, a push for a national monument can be initiated from the top through elected officials, federal or state agencies or other large organizations. From there, the proposal makes it way down to the local level. According to NonProfit Quarterly, these types of projects typically cost more and may not achieve benefits for the local communities.

Bottom-up movements characteristically involve a grassroots effort that begins locally then expands upward to larger local, state and federal agencies and groups. “With community-based initiatives, local people usually remain involved through caretaking the property. Often, this extends to community education and related benefits for the long term. This bottom-up conservation works well because — in part — it is a collaborative process, building on the organic relationships local activists have with the land.”

Stakeholders, Stakeholders and More Stakeholders

A key to success is involving community stakeholders in the process. One of the more overlooked and neglected steps is the identification of the stakeholders themselves. These may be user groups, organizations or individuals, and they typically fall into three groups: They may be involved in the nomination process, be affected by the nomination itself or have some amount of control over the nomination, such as elected officials.

“The process always starts with people who recognize the value of protecting something special,” says Alan Spears, director of cultural resources for the National Parks Conservation Association. Spears helped Virginia, Maryland, Ohio, Delaware, Illinois, Alabama and the District of Columbia achieve national monuments during the Obama administration.

He cites the designation of Fort Monroe on the Virginia seacoast as a good example of how local elected officials and diverse community groups — including Preservation Virginia and the Contraband Society (descendants of the regions enslaved population) — worked together to build support for national monument status when the site’s active military base closed. Fort Monroe’s early history involved American Indians, Captain John Smith and a famous military designer following the War of 1812 and evolved into a significant sanctuary for slaves seeking freedom. Spears said local citizens moved quickly following announcements of the base closure and rumors of plans to build a beach resort. Community organizers enlisted the assistance of the National Parks Conservation Association, a D.C.-based advocacy organization, to help develop strategy and engage political champions.

Creating a national monument requires legwork and tenacity. Spears says that the Obama administration scrutinized the reasons why community leaders believed a national monument was important and closely reviewed the breadth of community support. He cautions that building support for designating a special place is only the first part of the process. “Once the monument is created, the commitment and dedication from the community is essential.”

“The post-designation period,” says Spears, “is the real work of establishing a new park and when fulfilling the community’s hopes and vision begins.”

Case Study: Fight for Manzanar

It was 1942 when more than 110,000 Japanese American citizens, including men, women and children, were detained in military-style camps in remote locations across the United States. They were held there for 2½ years until a few months after the end of World War II. One of these camps was the Manzanar War Relocation Center situated in the Owen’s Valley of California. Annual pilgrimages back to Manzanar began in 1969 as a way to heal, and to remember what had taken place. Starting with this initial pilgrimage, a group called the Manzanar Committee formed and continues, to this day, to work to educate others so this type of tragedy never happens again.

One of the people interned at the camp, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, became one of the foremost leaders and activists with the Manzanar Committee. Many of those interned at the camp would not talk about their experience, but Embrey was among a handful of those who not only talked about it, but fought to teach others about the tragedy that occurred there. In 2004, Embrey spoke at the National Park Service’s Opening of the Manzanar Interpretive Center: “People ask me why it’s important to remember and keep Manzanar alive...my answer is that stories like [these] need to be told, and too many of us have passed away without telling our stories.”

Lynn Davis is the Director of Federal Policy and Legislation for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. Paula Jacoby-Garrett is a Freelance Writer and serves on several lands conservancy boards in southern Nevada.