.jpg) When it comes to comparing urban parkland, a rock-solid baseline has always been “acres per thousand,” as in, how many acres of parkland does your city have for every thousand residents? But often that’s not exactly the right question. In many cities, residents are only a part of the picture.

When it comes to comparing urban parkland, a rock-solid baseline has always been “acres per thousand,” as in, how many acres of parkland does your city have for every thousand residents? But often that’s not exactly the right question. In many cities, residents are only a part of the picture.

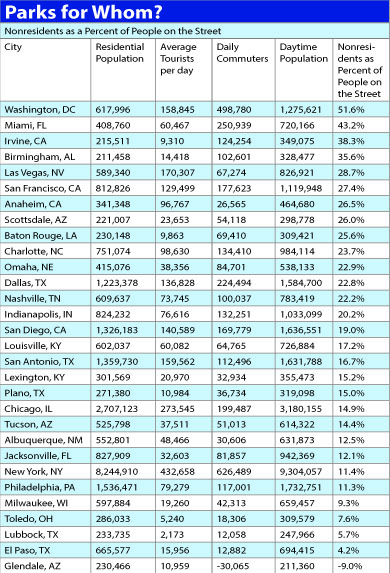

A city’s official population is, effectively, its nighttime population: the number of folks who sleep there, not counting those in hotels. But that number is not the most relevant for park managers since parks are generally daylight facilities. The better fact is acres of parkland for every thousand daytime urbanites (residents plus commuters plus tourists). The distinction is not trivial. Nor is there a standard multiplier by which it can be estimated — it’s got to be actually counted. In some cities, the nonresident population truly soars, while in others it barely registers a bump.

Take the District of Columbia. About 18 million tourists visit the nation’s capital every year, joining almost 500,000 daily commuters who pile into the city from the suburbs Monday through Friday. At 3 a.m. on a nontouristy weekend — say, a Saturday in early January — there are about 600,000 people in D.C., very few of them using a park. At noon on a bustling weekday — say, the Monday of Cherry Blossom Festival week, with both the deluge of commuters and flocks of tourists — there are about 1.2 million, most of them up and about, and many of them in parks. Many of the folks are playing, biking, sitting, eating lunch or walking to one of the museums on the National Mall (which is, after all, a park and the site of all those cherry blossoms). On an average day, more than one of every two people on the streets of Washington is a nonresident.

The Washington case is particularly extreme, but other cities also exhibit wild swings in population. Orlando, Anaheim, Las Vegas, New York and Boston are deluged by tourists, and Pittsburgh, Atlanta and Miami are particularly impacted by commuters. Even the resident population of Indianapolis — a midrange city — experiences a 20 percent jump from tourists and daytime commuters.

Obviously, visitors put a different kind of strain on city park resources than do full-time residents. Tourists may make little use of pools, recreation centers and dog parks, but they are a big factor in such downtown spaces as New York’s High Line and Chicago’s Millennium Park as well as signature destinations like San Diego’s Balboa Park and Philadelphia’s Independence Mall. As for commuters, they are a major midday presence in Boston’s Post Office Square and Washington’s Farragut Square.

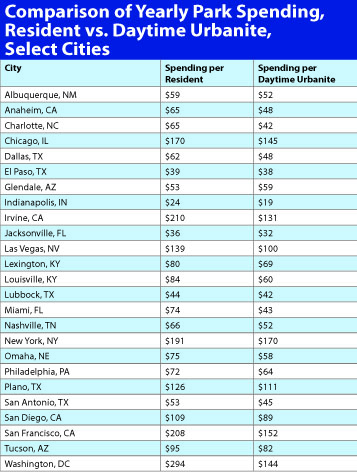

In some cases, the influx is the unnoticed factor that explains a city’s high parks budget. On a per-resident basis, Washington’s park and recreation spending came to a chart-topping $294 in 2012, but on a “per daytime urbanite” calculation, it dropped to a more realistic $144. San Francisco, another seemingly high-spending city, dropped from $208 per resident to $152 per daytime urbanite. Even these budgets are generous; in contrast, El Paso, Texas, which actually has a larger population than Washington but receives few tourists or commuters, spent $39 per resident and $38 per “daytimer.”

The impact of the nonresidents, of course, is most heavily felt in maintenance and upkeep. The National Mall takes a beating as if Washington were a city 10 times its size. New York’s Central Park receives more out-of-town visitors every year — 11.5 million — than almost every other park in the country gets from its own residents. The impact on grass, trees, paths, railings, steps, shrubs, flowers, soil compaction, roadways, water systems, fountains and trash removal is immense.

Of course, no one should begrudge the use of parkland by out-of-towners. Yes, there may be more shoulders to rub with, but parks, along with recreation programs, can serve as a very significant source of publicity, recognition and desirability for cities. These factors inevitably translate into revenue. Whether inspiring tourists through a visit to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park or refreshing downtown Atlanta commuters through lunches in Centennial Olympic Park, great urban green spaces are a substantial factor in a city’s attractiveness and its economy.

If heavy out-of-towner park use truly diminishes the experience for residents, the response should be the acquisition of more parkland, preferably with some of the funds derived from nonresidents. And therein often lies the rub. Many city councils treat their park systems as one-way streets, happily accepting money they indirectly bring in but tightly limiting the spending budget.

Park departments are funded mostly through the residential tax base, with small boosts coming from user fees and the occasional state or federal grant. Virtually all the agencies experience a major gap between what they get and what they need. Tourism and commuter revenue could help close that divide. But to get there, park advocates must make the case that parks are a significant cog in the tourism machine. This hasn’t been done yet, partially because tourism agencies themselves are surprisingly ignorant of the underlying reasons that visitors come to cities. They know how many people stay at hotels and eat at restaurants, and it’s easy to track how many come for conventions, but few study all the reasons the average visitor visits. Often it involves an event in a park or even the very park itself.

Meanwhile, most park departments themselves don’t have the funds to count and analyze their users’ places of residence or reasons for coming.

“It perpetuates the data vacuum,” says Texas A&M Professor John Crompton, who has written and spoken extensively about the problem and even served two terms on his city’s council to try to make some changes. “Time after time with things like sports tournaments, the park department has to apologize for a programming deficit while the tourism agency gets lauded for generating fantastic hotel and restaurant revenue — and it’s all from the same event!”

When park departments do count tourists, the data is usually limited to a few high-profile parks. Central Park, for instance, is thoroughly documented, thanks to the work of the Central Park Conservancy. The most heavily used park in the U.S., it received 37.5 million users in 2009, 31 percent of whom were not residential taxpayers.

Also in New York, Bryant Park is another closely monitored location. Based on 700 demographic interviews, researchers found that 51 percent of Bryant Park visitors are from New York City, 20 percent are from surrounding states and 29 percent are overnight tourists from more distant locations.

Similarly, in San Diego’s popular Balboa Park, a 2007 study funded by the Legler Benbough Foundation revealed that 65 percent of all August visitors were first-time park users — in other words, overwhelmingly tourists. (The average San Diegan visits the park six or more times a year.) Even more impressive, the survey found that fully 20 percent of tourists to San Diego said they came to the city so they could go to Balboa Park, and 75 percent of the tourists in the park said that Balboa was the primary reason or one of several reasons for coming to the city. In the mind of the tourist, San Diego and Balboa Park are almost inseparable.

Even much less famous parks can still be heavily impacted by tourists and commuters. San Francisco’s Alamo Square is not world-famous, but the iconic row of “Painted Ladies” Victorian houses is, and they are best viewed from the park across the street, which is what always keeps Alamo mobbed with people.

Perhaps the most thorough systemwide data collection takes place in Minneapolis and St. Paul, thanks to a requirement by the Metropolitan Council in order to receive funding. There they find that 45 percent of regional park users come from a different nearby jurisdiction — in other words, they are day visitors. About seven percent of visitors visit from outside the metro area — overnighters. Sadly, few other park agencies amass this kind of important information.

Not surprisingly, the visitation level is not simply incidental — the agencies work hard to achieve it. The Minneapolis Park Board, whose motto is “A City by Nature,” hosts major attractions like the Lifetime Fitness Triathlon, the National Pond Hockey Championships and the Luminary Loppet, as well as concerts and festivals. St. Paul hosts a large Winter Carnival in and around Rice Park.

While some park agencies struggle to stretch their regular budgets to meet the burden of tourists and commuters, others have managed to generate earnings from special events. The San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department requires organizers to cover direct costs of the massive Outside Lands Music Festival (70,000 attendees over three days) and the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival (300,000 attendees over three days) in Golden Gate Park. Those and similar fees end up providing 35 percent of Rec and Parks’ budget and have supported infrastructure investments, paid for gardeners, and funded scholarships and recreational programming.

Some park agencies in newer, low-density cities have built facilities specifically to host out-of-town visitors for sporting events. In Arizona, Tucson’s Kino Sports Complex, a massive regional tournament facility run by Pima County, brings in 35 college baseball teams each spring. With soccer, lacrosse, softball and field hockey facilities as well, the complex drives a steady stream of visitors, attracting millions of outside dollars.

Seeing the revenue flow from events is easy. Recognizing the broader concept of “urban parks tourism” is not. That’s where some park advocates accuse tourism officials of myopia.

“If we got credit for bringing in visitors and maybe even for bringing in some new residents, we would promote our parks to out-of-towners,” says Oklahoma City Park and Recreation Department spokeswoman Jennifer McClintock. As it is, “we won’t spend money to market programs that are free, since there’s no return on that investment.” Even in the city’s marquee parks, like Myriad Botanical Gardens and the Oklahoma City Zoo, programming and marketing efforts are aimed more toward the local population than out-of-town visitors.

It’s a vicious cycle. The park department is underfunded; it doesn’t have resources to undertake publicity; it doesn’t do promotion, even for its premier park; tourists don’t know about it and don’t ask; the tourism agency focuses on other icons of the city; the parks are perceived by politicians as having no economic multiplier effect; and the department remains underfunded.

While the park advocacy community repeats clichés like “You can’t have a great city without great parks,” that rhetoric is ineffective without hard facts, and those facts then need to be driven home to elected officials through the political process. One of the strongest pieces of factual information missing from the debate concerns the costs and benefits of park visitors.

Peter Harnik is the Director and Abby Martin is Research Coordinator of the Center for City Park Excellence at the Trust for Public Land. Additional research for this study was conducted by Katrina Flora.

PRORAGIS Park Values Calculator

The Park Values Calculator tools in PRORAGIS™ allow agencies to estimate the values that parks bring to their communities, capturing the potential economic impacts of improved air quality, water quality and stormwater impact mitigation. These economic impact estimates are based on published literature and allow agencies to provide powerful arguments to elected officials about the value of parks. NRPA is actively engaged in supporting research to refine and expand the tools in the Park Values Calculators.

Why Are the Numbers so Sketchy?

The question seems simple enough: How many out-of-towners (tourists plus suburban commuters) are on the streets of each of America’s major cities on an average day? To control for different-sized cities, we sought the ratio of visitors to residents.

Urban commuting data, compiled by the Census Bureau, is thorough and easy to obtain. Not so with urban tourism data. Unlike virtually every developed nation in the world, no government organization collects national numbers on leisure and business travelers. (The Department of Commerce tracks top U.S. destinations for international visitors, but that provides only a small piece of the picture.) Instead, tourism data is self-reported by each city’s destination marketing organization, and research methodology varies wildly. San José tracks only visitors arriving through its airport, Long Beach counts attendees at paid entertainment events, and a dozen other cities collect only economic impact data or hotel occupancy information. Some cities count only overnight stays, not day visitors. In some places “city” means city, whereas in many others it means metropolitan area, such as the eight counties around Pittsburgh or the 15 counties around Cincinnati.

Until there is a more unified and rigorous regimen for measuring urban tourism numbers and motivation, it will be difficult to fully understand the impact — or lack of impact — the park system has on the number of visitors a city receives.