It’s a tree disease with an almost biblical name—thousand cankers. Carried by insects, this fungal disease from Mexico is wreaking havoc on black walnut trees across the western United States. Although black walnuts are actually native to the eastern U.S., they were commonly planted in many western urban and suburban communities.

It’s a tree disease with an almost biblical name—thousand cankers. Carried by insects, this fungal disease from Mexico is wreaking havoc on black walnut trees across the western United States. Although black walnuts are actually native to the eastern U.S., they were commonly planted in many western urban and suburban communities.

The loss of entire species of trees from urban areas is not just an aesthetic concern. A recent study by the U.S. Forest Service found declining human health in areas hit hard by the emerald ash borer, which is estimated to have killed 100 million ash trees in the East and Midwest. One striking result of the study revealed that the borer infestation was associated with an additional 6,113 deaths related to illnesses of the lower respiratory system and 15,080 cardiovascular-related deaths in the 15-state study area over a period of 18 years.

Although many cities have maintained tree inventory records for decades, tree-canopy assessments offer a wealth of new information about the beneficial effects of trees on urban areas. Boise, Idaho, known as the “City of Trees,” recently participated in a canopy analysis after losing its black walnuts to thousand cankers and seeing a new mysterious decline in Norway maples.

“The tree inventory will give us an idea on a tree-by-tree or species-by-species or neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis—we know exactly where the trees are and what they are,” says Brian Jorgenson, Boise city forester. “But we don’t necessarily have a big picture of the city overall….The tree canopy study is looking at the canopy overall. You’ll be able to look on a broader basis—where are the trees in Boise? Where can we take advantage of the benefits that trees bring?”

i-Tree

Boise will soon be able to monitor the short and long-term effects of tree losses and replanting efforts with the help of canopy-analysis software called i-Tree. i-Tree is a public-domain suite of software tools (www.itreetools.org) developed by the U.S. Forest Service in a cooperative partnership with the Davey Tree Expert Company, National Arbor Day Foundation, Society of Municipal Arborists, International Society of Arboriculture, and Casey Trees. The tools allow communities to assess their percentage of canopy cover by using freely available satellite-based imagery or even aerial images from Google Maps.

“We’ve had the idea for more than 10 years since I’ve been here and, honestly, I think the technology is finally catching up to our desires on this,” Jorgenson says. “We can get down to where we can look at an entire city and determine what your percentage of tree canopy coverage is and even identify down to specific planting sites where you have room for more trees.”

Boise, situated in a desert, has only about 15 percent tree-canopy coverage, but that overall figure is somewhat misleading, according to Jorgenson.

“Boise has undergone a huge growth explosion in the last 20 or 30 years,” Jorgenson explains. “In the older parts—Boise’s north end—we’re looking at 30 to 40 percent tree canopy down there, but the city as a whole drops it down to 15 percent. So if you leave those old neighborhoods out, where are you at? Probably only 6 to 10 percent for the rest of the city. So that will help us determine where we want to see additional growth in the tree canopy.”

Often a tree-canopy analysis is performed on several neighboring communities at the same time. In the Willamette Valley in Oregon, an American Forests tree-canopy analysis in 2001 of the entire valley including Albany, Corvallis, Salem, and Portland revealed that the valley’s tree canopy has declined from 42 percent to 24 percent from 1972 to 2000. American Forests recommends a tree-canopy cover of 40 percent for urban areas in the Willamette Valley and lower Columbia River, but Albany’s current canopy cover falls well short of that level, so the city needed to set a more realistic goal.

“The goal is 25 percent canopy cover—right now we have 18 percent,” says Craig Carnagey, parks and facilities manager for the City of Albany. “Twenty-five percent seems to be a reasonable amount of cover based on historic coverage….Plus when you calculate in the environmental services, it seemed like you would really be maxing out your benefits from the canopy cover if it were around 25 percent.”

In 2005, the city hired a contractor to enter tree inventory data points into ArborPro, a GIS software program. Bringing in a contractor enabled the detailed tree inventory to be completed in just one summer month, rather than relying on volunteers and interns over a longer period. Now Carnagey can pull up any tree in the inventory database and see its species, size, condition, maintenance history, and even its photo in many cases. And, following up on the 2001 satellite canopy analysis, last summer a graduate student performed a more detailed i-Tree canopy analysis by recording tree cover at 190 random sampling sites in Albany. Carnagey notes that the tree inventory and canopy analysis are both useful tools.

“I think the i-Tree set of software is a really good tool to start out with,” Carnagey says. “It is good to have a detailed understanding of your urban forest through an actual inventory that does go through tree by tree—that’s really important from a management and maintenance perspective—but that cover benchmark is really important for planning for the future and for communicating to your public the value of trees.”

Money Does Grow on Trees

Although most people inherently understand the benefits that trees bring to communities, i-Tree enables users to quantify and maximize those benefits.

“Most cities are going toward the canopy cover approach to urban tree management,” Carnagey says. “Rather than just looking at just the trees in your forest and tracking those, you’re looking at the overall coverage, mainly because of the benefits that you can start to see from looking at the canopy cover in aggregate. There’s all sort of environmental benefits that you get, but also environmental services, like stormwater control and carbon sequestration. You can start to get a sense of what sort of savings in services you’re getting from the canopy cover once you know what the percentages are for your city.”

Using the National Tree Benefits Calculator (www.treebenefits.com), an analysis indicated that Albany’s urban forest intercepts 465 million gallons of stormwater every year, providing an essential service valued at $12.9 million annually. Carnagey estimates that each one-percent increase in tree-canopy coverage will require planting 5,400 shade trees at a cost of $800,000. However, that one-percent increase in canopy cover would add $716,000 worth of annual stormwater capacity, so even though the trees will take decades to mature, the eventual return on investment would be four times the cost.

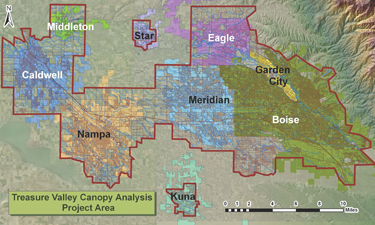

Back in arid Boise, Jorgenson notes that their initial tree-canopy assessment was driven more by air-quality issues than stormwater management concerns. The Treasure Valley area of Idaho, where Boise is located, is approaching its air-quality limits for ozone, and particulate matter is also high. In response, the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality began to build a coalition of organizations that would benefit from more information on the area’s tree-canopy coverage. The Treasure Valley tree-canopy assessment was funded by a USDA grant in cooperation with Idaho Department of Lands, local communities, the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality, Idaho Power, Boise State University, and several other partners.

“From having this information, we know what the benefits of trees are, and it needs to be considered as part of the solution,” Jorgenson says. “Not that planting trees is going to solve the world’s problems—we all know that’s not the case—it’s just another piece in the puzzle, another tool we can use to help control our air quality.”

Growing Your Canopy

i-Tree also features a new design tool that can help assess the benefits of trees down to an individual parcel of property. Using Google Maps, the tool allows users to see how tree selection, size, and placement will affect heating and cooling energy use as well as stormwater management. For example, Jorgenson envisions working with the public works department to identify areas like parking lots where trees could help lighten the load on existing stormwater infrastructure. And Idaho Power plans to start working with homeowners to determine areas where trees can be planted to help shade homes.

Jorgenson says, “I often look at trees as fourth utility or fifth utility, like electricity, sewer, and water. Trees are a utility that has a bottom line effect on your pocketbook, and they actually appreciate over time rather than depreciate.”

Both Boise and Albany have tree-planting programs utilizing citizen volunteers. Boise has its own nursery and provides homeowners with “street trees” to plant on their own property adjacent to the street, since much of the city lacks right-of-way planting strips. Although Albany has had a street-tree request program for many years, where residents can request a tree to plant in front of their homes, recently the city has shifted gears to where volunteers can pick a solicitation kit and go door to door asking their neighbors if they want trees to be planted in the front right of way. Neighborhoods can also develop their own tree-planting plan and apply for city funding to purchase the trees and host a planting work party.

Carnagey says, “We can go to the neighborhood associations and say, ‘We want to help your neighborhood in terms of tree canopy, and here’s where there are some opportunities for the city to work with you. Or you can work independently with your constituents to plant trees in your neighborhood and increase the value of your homes and all the environmental good stuff that goes along with it.’”

Elizabeth Beard is Managing Editor of Parks & Recreation.