The Zika virus has finally begun to spread in the U.S. through transmission by mosquito bites. Up until very recently, all known cases of Zika were considered to be “travel cases” — that is, they were contracted in a foreign country and people who were infected brought the disease into the U.S. There are currently about 3,000 such cases of Zika that are known and being monitored by local health departments and CDC.

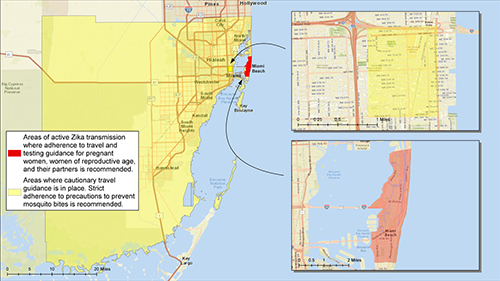

Beginning in August 2016, however, the first locally transmitted cases were discovered in and around the City of Miami, and more recently, in Miami Beach. There are currently 43 known cases of local transmission of Zika in south Florida. In addition to mosquito-borne transmission, there are a small number of cases found to be transmitted sexually, expanding the possibilities of how this disease can be contracted.

SOURCE: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/index.html

As the disease spreads northward and westward across the U.S., park and recreation agencies have become concerned about the potential of the disease being transmitted to the public and to park and recreation workers. With these concerns in mind, here are some simple recommendations for what you can do if Zika is suspected or confirmed in your local area:

1. Identification: Before you consider taking any kind of control measures, you need to know if the Zika-carrying species of mosquitoes, principally Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, are actually present in your parks. Confirmation and notification will likely come through your local public health agency or through your local mosquito control unit (which may be a part of a state government agency). You should learn what branch of government your mosquito control unit is under and reach out to them well in advance of any confirmed reports. Some states and localities have developed unified Incident Command Structures (ICS) to bring all affected agencies under one umbrella. Park and recreation directors should make sure parks and recreation is represented in any task force or working group on Zika control.

2. Surveillance: Identifying the Aedes aegypti mosquito is not an easy task and generally can only be done through trapping and lab identification. However, it is possible for parks and recreation staff to identify the egg and larval form of the A.aegypti mosquito in standing and stagnant water. In advance of a Zika outbreak in your community, parks and recreation staff in urban areas should begin to identify possible locations of standing water that can be drained or controlled including rooftops, gutters, areas around drains, boats and boat covers, flower pot saucers — every single source of standing water — and prepare staff for the time you may need to inspect and drain these sources.

3. Control: The simplest and best means of control, according to Joe Conlon, mosquito control expert of the American Mosquito Control Association (AMCA), is to eliminate all sources of standing water around buildings. Most often, the Zika-carrying mosquitoes, A.aegypti, will be found in urban areas around buildings or in trash receptacles. Checking and draining any containers with standing water is the best way to control the spread of Zika carrying mosquitoes. Joe Maguire, natural resources manager for Miami-Dade County parks and recreation, says that their staff does weekly inspections of all their facilities and grounds to find and drain every source of standing water. He says it has been a large unanticipated commitment of staff time, but he feels confident that their parks and recreation facilities are doing all they can to prevent the spread and transmission of the Zika virus.

Most park and recreation agencies do not normally do their own mosquito control spraying. This is often the responsibility of city, county or state mosquito control units, who may or may not notify park agencies when they spray in or around parks. Park managers should learn who will be spraying (governmental mosquito control units or contractors) and pay careful attention to what type of insecticides are being sprayed, where they are spraying, and what times of day they are spraying.

A recent news report identified the mass death of more than three million bees in Dorchester County, South Carolina just after the spraying of a pesticide that contains Naled, a commercial insecticide that is very effective in controlling mosquitoes, but is also extremely toxic to bees and other pollinators. Unfortunately, aerial spraying or broadcast spraying for mosquito control can be very damaging to beneficial insects if it is applied incorrectly. As far as parks go, you should proactively notify your mosquito control units of the presence of pollinator habitat or pollinator gardens as well as other rare or threatened wildlife species that could be impacted by large scale spraying, and request that they do not spray such areas but rather consider very localized treatments at non-peak times to prevent death of foraging and nectaring insects.

NRPA has some very good resources on Zika prevention and control that are specific to parks and recreation:

Also, visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website for more information and toolkits to learn more about the spread of Zika in the U.S.

Richard J. Dolesh is NRPA's Vice-President of Conservation and Parks.