Playgrounds have always been a racial justice issue, so let’s treat them like one.

This blog post originally appeared on Kaboom! Stories and has been cross-posted here with permission.

Racial exclusion in recreational spaces has denied Black kids the essential benefits and simple joys of play for generations. The history of segregation in playgrounds, parks and swimming pools has been central to the broader fight for racial justice in America from the early 20th century up to today.

Legal and de facto segregation, along with racialized disinvestment, have long restricted the ability of Black families, in particular, to freely live and move in neighborhoods and public spaces, including recreational amenities. This remains the case even though efforts led by Black Americans to integrate playgrounds and amusement parks have always been at the center of the broader struggle for civil rights.

“You suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky…” -Letter from a Birmingham Jail, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Playground Segregation in our Nation’s Capital

In the summer of 1945, the Washington, D.C., Board of Recreation issued an explicit rule officially segregating public recreation facilities under its control, most of which were already informally segregated. Their circular argument was one that segregationists had used for generations: integrated playgrounds would “disrupt racial harmony” and lead to violence.

The focal point of the struggle in D.C. was around Rosedale Playground, which opened in 1913 as a whites-only playground despite its location in a neighborhood where Black families had lived since the late nineteenth century.

Following the citywide segregation order, four Black boys from the neighborhood were arrested when their ball hit a street lamp while they played outside of the playground that they were barred from entering. Protests grew, reaching a new pitch in 1952 when a Black boy climbed a fence to swim in the Rosedale pool and drowned.

Established civil rights organizations got involved as the story began to garner significant national attention. Playgrounds became a powerful symbol of the need for racial equality because they were about something as basic as allowing kids to be kids.

After fighting broke out with counter-protesters in 1952, the D.C. Recreation Department closed the Rosedale playground. But kids took matters into their own hands. The Afro-American newspaper reported that a few days after the playground was closed, more than 100 neighborhood kids climbed over and under the fence in defiance of officials. Police and city employees watched stunned.

“Faced with the children’s apparent determination to use the playground and the refusal of police to intervene, recreation employees retired to the shade of the locker building, where they watched colored and white children playing together without friction.” -D.C. Children Defy Ban, Play At Restricted Spot (Afro-American, Sep 20, 1952)

Later that year, the Recreation Board reversed its decision and announced it would open the playground to everyone, which happened 6 months later in the spring of 1953, just one year before the decision in Brown v. Board of Education ordered the desegregation of public schools nationwide.

Caption from article clipping: Some of the 100-odd children who played at disputed Roswdale playground Thursday without incident. White children joined them. One policeman said, “I couldn’t arrest them, they were having such a good time.”

Access and Belonging: Still an Issue Today

The laws changed, but privatization, racialized disinvestment and harassment continue to keep Black people out. The story of Black birdwatcher Christian Cooper, who was harassed and threatened in Central Park last year by a white woman, is only one example of how Black people are systematically excluded from or made to feel unwelcome in spaces like parks and playgrounds.

The consequences fall on a spectrum just like racism anywhere else: exclusion from decision-making and programs, subtle glances of suspicion, overt threats, police intervention and even death in the case of kids like Tamir Rice, a child killed by police while innocently playing at his neighborhood playground, or Iesha and Clendon Elmore.

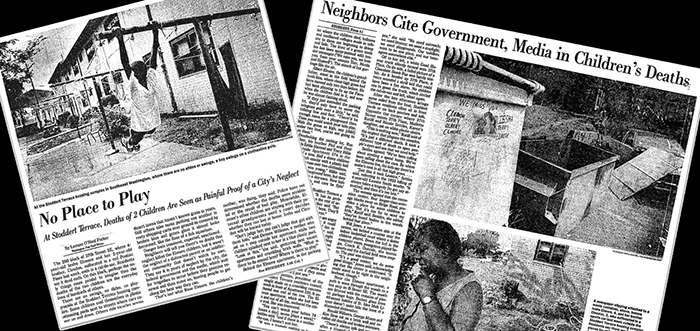

It was a hot July day in 1995 when Iesha and Clendon went looking for a place to play in their Washington, D.C. neighborhood. With no playground in sight, they turned to a nearby abandoned car and climbed in. Faulty locks trapped the two children inside and, tragically, they died from heat exhaustion.

Clippings from The Washington Post, No Place to Play, detailing the tragedy of Iesha and Clendon Elmore.

“Neighbors will tell you there’s no doubt that neglect killed the Elmore children, but it wasn’t the neglect of a distracted parent or an indifferent community that doesn’t watch its own. They say it is years of neglect by the city, the federal government and the media, which wait for tragedies to occur before they promise renewal and then move on, leaving people to get along the best way they can.” -O’Neal Parker, Washington Post 1995

It was this story that first sparked the founder of KABOOM! to take action. A few months later, the first KABOOM! playground was built in the Congress Heights neighborhood, not far from where Iesha and Clendon lived.

The cruel reality for too many Black and brown kids is that they not only lack safety and freedom within their own communities, but are also held within a system of adultification that keeps them from being kids. Biased imagery and beliefs mark Black children as older and more culpable than their white counterparts. The chronic stress that results is immeasurable.

Research confirms what parents already know: play is a developmental necessity that sparks social, emotional, and physical growth. But playgrounds are also about the basic need to belong. In Black and brown neighborhoods that have been subjected to chronic disinvestment, kids can miss out on having a joyful place where they feel safe. Addressing this need is as important to their well-being as tackling other disparities in housing, education, and health.

It’s time that we learn from the history of racial exclusion and make investing in spaces for Black joy a centerpiece of rebuilding efforts in the coming months. Playgrounds have always been a racial justice issue, so let’s treat them like one.

For us at KABOOM!, that means putting community and racial equity at the center of everything we do. It means starting with working alongside communities to understand their needs and assets to join them in creating better outcomes for kids. We follow where those hundreds of kids who jumped the fence at the segregated Rosedale Playground led, and where movements fighting for Black lives lead today.

Kevin Paul is the Senior Communications Manager at KABOOM!, a national nonprofit that works to end playspace inequity. KABOOM! has built 17,000+ playspaces, engaged more than 1.5 million community members and brought joy to over 11 million kids.